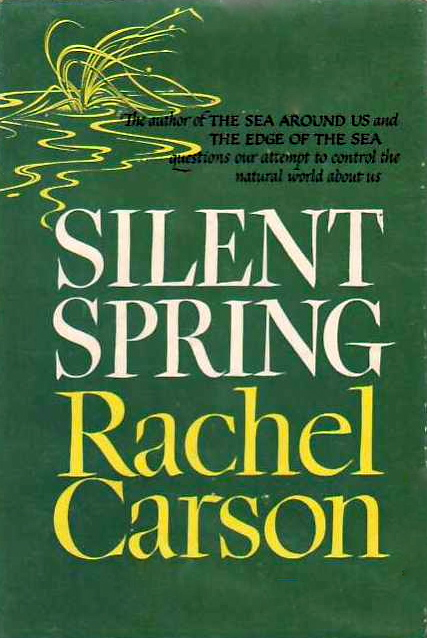

Rachel Carson’s ground-breaking book “Silent Spring, published in September 1962, ignited modern U.S. environmentalism and resulted in new laws for environmental and public health protection in the United States. Two days before it came out, President Kennedy signed his approval for the so-called “rainbow herbicides” (Agents Orange, White, Purple, Green, Pink and Blue, named for the colored bands on the herbicide barrels ) to be sprayed on Vietnamese crops.

Rachel Carson’s ground-breaking book “Silent Spring, published in September 1962, ignited modern U.S. environmentalism and resulted in new laws for environmental and public health protection in the United States. Two days before it came out, President Kennedy signed his approval for the so-called “rainbow herbicides” (Agents Orange, White, Purple, Green, Pink and Blue, named for the colored bands on the herbicide barrels ) to be sprayed on Vietnamese crops.

President Kennedy read “Silent Spring” in a serialized version for The New Yorker in the summer of 1962. Like millions of others, he was compelled by her message and had Carson invited to the White House. And, yet, what Carson exposed and condemned in our environment — the indiscriminate chemical war on nature with insecticides and herbicides as weapons — did not apply to Vietnam. The preoccupation of his administration was “image” — lest the United States be seen by the world as conducting chemical warfare in Southeast Asia.

As the war widened in 1965 under President Lyndon Johnson, spraying increased exponentially, creating intensive and widespread environmental abuse that gave rise to the term “ecocide.” Search-and-destroy tactics in rural hamlets during Johnson’s ground war years resulted in millions of refugees flooding Saigon, relegated to slums and extreme poverty — precisely the conditions in U.S. cities that he hoped to overcome with his vaunted Great Society and War on Poverty programs.

By 1966, over 5,000 American scientists, among them Nobel Prize winners, condemned the use of chemical warfare agents in Vietnam. The U.S. herbicide program ended in 1971 when Richard Nixon’s administration was forced to disclose covered-up research data which revealed that one of the herbicides in Agent Orange caused birth deformities in lab animals.

The major points of “Silent Spring” can be summarized accordingly: Modern pesticides are, in essence, biocides; and the post-World War II agricultural industry is waging a “peacetime” chemical assault on nature. When forests and crops are sprayed, the drift of pesticides contaminates the web of soil, groundwater, streams and the food chain, from insect larvae to worms, birds, fish and humans.

The regulatory system, by permitting toxic chemical residues in commercially sold food, authorizes contamination of public food supplies and promotes an unjustified impression that safe limits have been established and are being adhered to. “Tolerances,” or the allowable chemical residues on food, are a method of slow poisoning sanctioned by the government.

Just as Carson anticipated, the industry drew its guns even before her book was published. The Montsanto Chemical Co., a major manufacturer of domestic-use pesticides and the largest manufacturer of Agent Orange, commissioned a parody entitled “The Desolate Year” — portraying a dystopian world of pestilence and famine without pesticides — and rushed the galley sheets to newspaper editors and book reviewers throughout the country to beat the “Silent Spring” publication date.

Despite fierce and heavily financed opposition by industry critics, “Silent Spring” swept through U.S. society with the force of a 500-year flood, resulting in sweeping environmental change.

By 1970, the federal government, under Nixon, created the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. In the same decade, Congress passed a rapid succession of environmental laws and amendments governing drinking water, air pollution, pesticides, hazardous waste and coastal areas.

A double standard prevailed throughout the American war in Vietnam, though. The lauded rights of American citizens to environmental protection and public health did not apply to Vietnamese upon whose country we perpetrated ecocide, with 20 million gallons of herbicides.

As a senator, Kennedy co-sponsored the Cape Cod National Seashore Bill and as president, he championed the Wilderness Act for the preservation of priceless coastal and forest environments. Yet in Vietnam, the herbicidal warfare program he initiated destroyed nearly 40 percent of coastal mangrove forests, the inestimable marine nurseries of that country; and more than five million acres of upland forests and agricultural lands, altogether about 20 percent of the forest cover.

With intense reforestation, the centuries-old triple canopy tropical forests, famed in Asia for the diversity of their wildlife, will take a hundred years or more to restore to pre-war conditions, at an estimated cost of $3 billion.

Had Rachel Carson lived, no doubt she would have been one of those 5,000 scientists who signed a petition in 1966 publicly protesting the chemical warfare in Vietnam. “The chemical weed killers are a bright new toy,” she wrote in “Silent Spring.”

“The agricultural engineers speak blithely of chemical plowing in a world that is urged to beat its plowshares into spray guns.” This technocentric mindset that advocated chemicals as weapons on farms, pastures and forests set the course of war in Vietnam. Chemicals — herbicides contaminated with dioxin as well as napalm — were our weapons of mass destruction.

Pat Hynes of Montague is a former environmental engineer and professor of environmental health. She is the author of “The Recurring Silent Spring” (Pergamon Press, 1984) and recently visited Vietnam to investigate the environmental and health legacy of Agent Orange. Frances Crowe of Northampton counseled hundreds of young men on conscientious objection during the Vietnam War.