by Anna Gyorgy, Traprock

Download here as pdf. A shorter version of this piece was printed in the July 23rd edition of the Montague Reporter, p. A4, online at: https://montaguereporter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/July-23-2020.pdf

Anniversaries are times to reflect and remember. They also help relate the past to the present.

This August 6-9 is the 75th anniversary of the only use of atomic weapons in war. Two bombs of previously unimaginable power destroyed two Japanese cities, killing around 200,000 people. The devastation then, and arms race since, are remembered each year in calls to abolish nuclear weapons.

This is a year of racial awareness, movement and action, and hopefully major social, economic and political change. Black Lives Matter.

It is also the 400th anniversary of the start of settler colonialism in our state and region. The suppression, eviction and near extermination of native peoples is also being examined anew, as reflected in new success in decades-long campaigns against widespread use of racist symbols in schools, city names and more. And newer campaigns against environmental racism, in the form of pipelines and projects endangering communities of color, as well as the planet.

So it is fitting and important to look at the the atomic bombings through the lens of race. It isn’t hard.

Our first gaze is at the racist objectification of the enemy. As well-known Filipino academic, environmental activist and author Waldon Bello wrote recently: “The war in Europe waged by the U.S. during the Second World War was promoted among the American public as a war to save democracy. This was not the case in the Pacific theater, where all the racist impulses of American society were explicitly harnessed to render the Japanese subhuman.

This racial side to the Pacific War gave it an intense exterminationist quality.” (1)

Both at home and abroad, as Americans of Japanese descent were put in prison camps, “something that was unthinkable when it came to Americans of German or Italian descent, though Germany and Italy were also enemy states,” writes Bello.

“But perhaps,” he continues, “the most radical expression of the racial exterminationist streak of the American war against Japan was the nuclear incineration of Nagasaki and Hiroshima in August 1945, an act that would never have been entertained when it came to fellows of the white race like the Germans.”

In their “At War with Metaphor: Media, Propaganda, and Racism in the War on Terror,” authors Eris Steuter and Deborha Wills write that: “Acclaimed 2nd World War correspondent, Ernie Pyle, was transferred from Europe to the Pacific in February 1945 and wrote: “In Europe we felt that our enemies, horrible and deadly as they were, were still people. But out here I soon gathered that the Japanese were looked upon as something subhuman and repulsive; the way some people feel about cockroaches or mice.” (2)

The racist attitudes against Japanese expressed in the media and echoed widely, were keenly felt by prominent African-American intellectuals and leaders. “Such criticism,” wrote historian Barton Bernstein in 2018, “was far more likely in 1945-46 among such black Americans, including especially black writers, than among their liberal white counterparts in the United States.”

For example, novelist and journalist Langston Hughes, who “on Aug. 18, 1945, condemned the bombings and also suggested racial motivations.” In his column in the famous Black newspaper Chicago Defender, “he obliquely asked why the $2 billion expended on the A-bomb project could not instead have been used to help clean up slums in America, particularly in African-American neighborhoods.”

Among the well-known African-American critics of the atomic bombings in 1945-46 were leading civil rights activist Bayard Rustin; the Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, also a Democratic congressman from Harlem; and novelist and author, Zora Neale Hurston.

“In 1945-46, possibly the harshest criticism of the atomic bombings by any notable African-American was from Hurston. Writing to a longtime associate, Claude Barnett, the founder and chieftain of the Associated Negro Press, probably the leading African-American news syndicate of the time, she bitterly complained that the press had been too soft in its treatment of Truman. She regarded him as a killer. She called Truman “the BUTCHER OF ASIA,” putting those three key words in capital letters in her typed letter.”(3)

The most definitive study on this history is Vincent J. Intondi’s 2015 “African Americans Against the Bomb: Nuclear Weapons, Colonialism, and the Black Freedom Movement.”(4)

Some of his key points were summarized by Beyond Nuclear’s Linda Pentz Gunter in a widely published article “Why Japan? The racism of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings.”

She quotes Intondi: “Since 1945, black activists had made the case that nuclear weapons, colonialism, and the black freedom struggle were connected.”

“African Americans recognized colonialism ‘From the United States’ obtaining uranium from the Belgian-controlled Congo to France’s testing a nuclear weapon in the Sahara’, Intondi writes. It was the use and continued testing of the atomic bomb, ‘that motivated many in the black community to continue to fight for peace and equality as part of a global struggle for human rights.’ ”

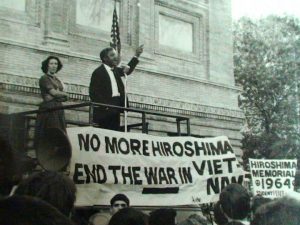

“Those who joined the struggle against nuclear weapons included Martin Luther King, Jr., of course, but also W.E.B. Du Bois, Paul Robeson, Marian Anderson and many others. Yet it is rarely their faces that are evoked when there is discussion of the Ban the Bomb marches or, later, the rise of SANE/Freeze.”(5)

Sustained Black opposition to the destruction in 1945 was revealed in a May, 2017, CBS news poll taken after President Obama’s visit to Hiroshima. It found stark differences in opinions about the bombing: “Americans are divided by gender, race, political affiliation, and age. Most white Americans, most men, and most Republicans approve of the U.S. dropping atomic bombs on Japan in World War II, while more non-white Americans, most women, and most Democrats disapprove. Americans under 45 are more likely to disapprove of the U.S.’s actions, while older Americans 55 and up tend to approve.”(6)

Turning to the extensive effects of nuclear weapons on Native Americans, we hear from indigenous author-activist Winona LaDuke. In her preface to the Uranium Atlas 2020, published this July 16, the 75th anniversary of the Trinity open air atomic test, she writes:

“More than three thousand Diné, who are also called Navajo, worked in the uranium mines in the 1950s, without special work clothes or any kind of radiation protection. Covered in radioactive dust, they walked home to their families – and without knowing it, contaminated their loved ones. People are still dying in Dinétah, the land of the Navajo. The danger is not contained, since almost a thousand abandoned mines still contaminate the region.”

The Atlas presents a readable and comprehensive look at this element, and the dangers associated with it. Dangers kept secret from the workers, who were also considered both essential and disposable. “At least 70 percent of the uranium in circulation worldwide,” it reports, “is mined on the land of Indigenous communities and tribal peoples.”

The Uranium Atlas is a comprehensive view of how indigenous peoples worldwide have been affected by nuclear development. It is online at https://beyondnuclearinternational.org/2020/07/19/mapping-uranium/ (7)

From the Uranium Atlas 2020

The English version was released on July 16, 2020, the 75th anniversary of the first “Trinity” test of a nuclear bomb, in the New Mexican desert. Its North American distribution was sponsored by the national Native initiative Honor the Earth

Where was uranium mined? …”almost exclusively on Indigenous lands; who was in harm’s way during atomic tests — almost exclusively communities of color; and where nuclear industries want to dump their waste — in the case of North America and Australia, once again on indigenous lands.”

The Atlas provides “a narrative of discrimination and colonial abuse; of people, their lands and their values.

We learn that Indigenous peoples on different continents use similar prophetic imagery to warn against extracting uranium from the ground.

In Australia it is the rainbow serpent, whose sleep must remain undisturbed or forces will be unleashed with dire consequences.

For the Diné (Navajo), it was a choice between the yellow dust of corn, or the yellow dust of uranium. Corn pollen would secure their life. The other yellow powder would endanger it and should be left in the ground.

For the Dene of Canada it was a cautionary warning of sticks dug from the ground to be carried away by an iron bird who would rain death on others far away.

For the Western Shoshone, it is the serpent swimming westward at Yucca Mountain, Nevada, where the end product of uranium’s use — high-level radioactive waste — could be dumped.

The price for not leaving it in the ground is played out across the pages of the Uranium Atlas.”

The 52 page Atlas is available as a free download here.

Footnotes

1. July 7, 2020

The Racist Underpinnings of the American Way of War by Walden Bello, Counterpunch

2. At War with Metaphor: Media, Propaganda, and Racism in the War on Terror; 2008, Erin Steuter, Deborah Wills, p48)

3. Opinion: Prominent African-Americans opposed atomic bombings

Aug 4, 2018, By Barton J. Bernstein

4. Associate Professor of History and Director of the Institute for Race, Justice, and Community Engagement at Montgomery College in Takoma Park, Maryland. From 2009-2017, Intondi was Director of Research for American University’s Nuclear Studies Institute in Washington, DC. His research focuses on the intersection of race and nuclear weapons. He is the author of the book, “African Americans Against the Bomb: Nuclear Weapons, Colonialism, and the Black Freedom Movement” with Stanford University Press, 2015. See also his recent piece: https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2020-07/features/reflections-injustice-racism-bomb

5. Why Japan? The racism of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings

Linda Pentz Gunter 17th August 2016 The Ecologist

6. CBS News, May 27, 2017, By Sarah Dutton, Jennifer De Pinto, Fred Backus and Anthony Salvanto

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/cbs-news-poll-what-do-americans-think-of-the-1945-use-of-the-atomic-bomb/

7. https://beyondnuclearinternational.org/2020/07/19/mapping-uranium/

Trinity Test, July 16, 1945